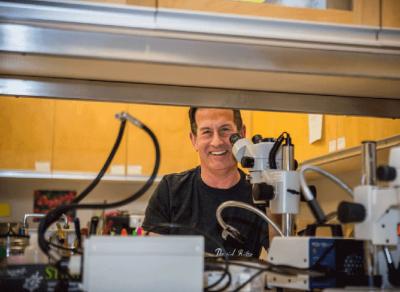

Carl Withler

Modernizing BC Agriculture

Agrologists working for the BC Public Service are shaping how agriculture in BC can grow the economy

The modern apple orchards of the Okanagan don’t look like the orchards of old. Instead of fields of big, wide trees with lots of room between them, the trees grow densely in tight rows like hedgerows. They are narrow and not much taller than the pickers, who can easily reach the dozens of red- and yellow-marbled fruit the trees bear in abundance.

Instead of producing 25 bins to the acre of apples, new orchards produce 70 bins, says Carl Withler, a treefruit and grape industry specialist with the Ministry of Agriculture’s Sector Development Branch in Kelowna.

Planting these new orchards is costly, but “it pays off,” he says. “Where you might get 12 cents a pound for older varieties of apples like Macs, you’ll get 43 or 47 cents a pound for Ambrosias or Honeycrisps.”

Part of Withler’s role is to encourage farmers in BC to move away from less profitable varieties of treefruit and grapes in favour of more profitable ones. He is the ministry’s representative on the $1.5 million per year Treefruit Replant program.

“Think of a Mac apple,” he explains, referring to the red and green McIntosh apple Canada has been known for since the nineteenth century. “It’s fantastic when you pick it off a tree. When you bite into it, juice drips down your face. After a month, it goes punk and soft; it browns and bruises easily. Newer varieties, Ambrosias for example, they’re crisp off the tree. You can keep them in cold storage. And they taste almost exactly the same months later.” And, people will pay a premium price for them, which is good for farmers and the economy.

Apples aren’t the only fruit in Withler’s portfolio; he also leads the export program for the millions of BC cherries sold into California each year and works with grapes in BC’s thriving wine industry.

Withler knows his job sounds romantic: walking through orchards, shiny red apples peeking out from behind green leaves, or inspecting firm grapes destined to be crushed into wine. The reality is that most of his work these days is administrative, but every once in a while he has what he calls a “golden day,” when he gets to walk through the orchards of fruit trees.

In the Field

Moving into an administrative role is a natural evolution after more than 30 years in the industry, Withler says. His early years with the BC government were high action and spent in the field. He started as a summer student with the Ministry of Agriculture in 1984. One day, he was out in the field when he saw “a great big pencil of black smoke.” It was a forest fire. “I thought, I’ll be darned, I want to be a fire fighter.”

For the next two summers, he worked as an initial attack crewman and later a crew leader for the Ministry of Forests. For the next decade, he continued to fight fires part time while he worked full time with the Ministry of Forests, first in Alexis Creek and then in 100 Mile House and Grand Forks.

The Apple Doesn’t Fall Far From the Tree

Withler credits his dad with inspiring his career path.

Ira Withler was a long-time regional manager with the Ministry of Environment. A fisheries biologist, he earned a master’s degree in natural resource management from Michigan State University in the early ’70s, taking his family, including five-year-old Carl, born in Victoria, to the United States for a few years before settling in Williams Lake.

“I travelled around with my dad for his work. We went to Bella Coola, Anahim Lake, 100 Mile House, all over the place. I listened to him and learned about his work, and it really influenced what I wanted to do,” Withler says. “I knew I wanted to work outside in some sort of natural resource field, but I didn’t know what it was.”

When it came time to choose a course of study, he left it up to providence—and the alphabet. He opened the University of British Columbia’s course calendar and went down the list, stopping at the first program with an outdoor component that he had the prerequisites for. The winner was agriculture, in the bachelor of science program.

“I might have been a forester if the alphabet started with F,” he jokes.

After graduating in 1988, he became a professional agrologist, a designation obtained through articling and gaining experience in the field. Range agrologists in the forest ministry develop management plans to protect the province’s rangelands, a vital source of food for grazing cattle and ungulates. Business owners in the cattle industry can apply for tenures and permits to have their cattle graze on Crown land. Range agrologists ensure the land is foraged in a sustainable way to protect the environment.

The career proved a great fit for Withler. “You get to deal with the ranching community, you get to be outside, you get to make some decisions along the way, you get to run projects. It was exciting and fun.”

Eventually, he took a position in Grand Forks as a range officer, where he stayed for 17 years. At one point, his position was split between range officer and recreation officer, as he became involved in improving rustic campsites and forestland trails.

Being a recreation officer was another romantic title, says Withler, who snowboards and mountain bikes in his spare time, as well as coaching his teenage sons’ soccer teams.

In 2003, Withler’s Grand Forks office was closed, leaving 43 employees out of work. Withler and his wife had just built a new house and had the first of their two sons, but they had to leave the community to find work elsewhere.

Withler was hired as a regional agrologist with the Ministry of Agriculture in Kelowna, the position he held until moving into the treefruits and grape specialist position, which he plans to stay in until retirement.

Giving Back

A member of the PEA since the early days of his career, Withler became active in the union in order to give back to an association that “has been good to me.”

For more than 10 years, he has been a local rep, and he recently ended four years as the chair of the Government Licensed Professionals chapter of more than 1,200 foresters, engineers, agrologists, geoscientists, psychologists and more.

He has a strong belief in equality, which made participating in the PEA a natural role for him. “As I worked through my career, I could see there were pretty significant inequities in hiring practices that concerned me,” he explains, adding that he “was—and am—quite concerned for the wage scale for PEA and GLP members.”

He appreciates the training opportunities offered by the PEA and has attended union conferences to further his education around labour.

Land, Food, Economy

Reflecting on his work these last few years, Withler says the connection between land, food and the BC economy fascinates him. “To be able to source food locally is a neat thing,” he remarks.

He and his wife’s family have owned an orchard in Osoyoos for 25 years, where they grow peaches in the backyard, raise rabbits, buy pears from a friend and buy locally raised beef and lamb.

“I think that people undervalue what agriculture does for this province,” he says. “Every year, in the Okanagan and Creston, we produce about $83 million of cherries and $200 million in apples. We export them around world, from Singapore to Berlin and all points in between. All that money comes back to the province of British Columbia, and we sprinkle it up and down the Okanagan and the Creston Valley. It happens year after year, and it’s expanding.”

He says Williams Lake has small plantings of apples and peaches, and the Thompson River drainage will be home to 200 acres of cherries starting in 2018. Not too long ago, those regions did not seem like they’d be part of the modern BC treefruit industry.

“It’s really neat to see. I hope agriculture continues to seek out opportunities to produce food for the province of BC and around the world,” he says.

Even after 34 years, Withler’s enthusiasm for his work is unmistakable. “It’s been a good career, trying to do good things for the people and the province.”