Menu Toggle

Government Licensed Professionals: BC’s Experts

From professional oversight to emergency response, public service professionals are critical to the work of the BC Government.

More than 1,800 Government Licensed Professionals work for numerous ministries and agencies across British Columbia, employed by the provincial government. As BC’s experts these agrologists, engineers, foresters, geoscientists, lawyers, pharmacists, psychologists, and veterinarians play a vital role in ensuring the safety, sustainability, and resilience of our province.

A strong and stable province relies on the dedication of these professionals. They oversee everything from infrastructure development to environmental protection. They also provide regulatory oversight of projects that are carried out by the private sector, ensuring adherence to strict safety, environmental, and ethical standards. Their expertise helps prevent costly failures, protects the public interest, and upholds the integrity of the province’s long-term investments.

Yet the public service continues to face ongoing challenges in recruiting and retaining qualified professionals because of:

- Compensation – When compared with public service jobs at the municipal and federal level, as well as many other provinces and private sector jobs within the province, BC public service professionals are compensated less. This is frequently cited as the main reason why professionals leave the BC public service.

- Burnout – These experts report high rates of concern with their ability to meet the mandate of their ministries. This leads to stress and burnout. This burnout is further heightened by the conditions faced by members involved in emergency responses such as wildfires, flooding and slides.

- Position vacancies – Without compensation structures to allow for career development and progression, these professionals are forced to leave the public service to further their career growth.

Foresters: Growing BC’s future forests

BC’s professional foresters help grow resilient trees to withstand climate change.

In the Bear Lake region north of Prince George, an expanse of pine, spruce, Douglas fir and alpine fir grows strong and resilient. The tree species were carefully selected by professional foresters in British Columbia to produce a site that could sustain variety, withstand climate change and support the ecology and wildlife of the region—mammals, fish, birds, insects and vegetation. Standing in that forest today, Larry Fielding, a woodlands supervisor with BC Timber Sales (BCTS), is awed at the last 15 years of bountiful growth. He helped reforest the site around 2010.

“It can be difficult for a reforested site to support that many different tree species,” Fielding explains. “But we chose trees that were ecologically suited for the site, and everything is growing really well. It gave me confidence in our work, seeing this healthy, resilient forest.”

The Bear Lake site is an example of successful reforestation that is taking place across the province. Fielding is one of 550 registered professional foresters working in 33 communities in the province for BCTS, part of the Ministry of Forests. Based in Prince George, Fielding became a registered professional forester in 2006, after graduating from the University of Northern British Columbia. He started with BCTS in 2007, helping to sustainably maintain forests on Crown land, which makes up 94% of the province’s total area of 944,735 square kilometers. A woodlands supervisor since 2009, his work focuses on silviculture as well as supervising a team of professional foresters.

“Right now is an exciting time in forestry because there’s a real focus on diversity, wildlife habitat and a lot of different values—and not just timber values,” he explains. “We’re trying to balance economic, cultural, social and biological values. We’re listening to the public, Indigenous people and stakeholders about what they value and what they want to see on the land base.”

Professional foresters in the public service in BC are members of the PEA in the Government Licensed Professionals chapter. Educated in the science of forestry, they play a crucial role in maintaining healthy forests, which is critical to the province’s environmental and economic wellbeing. They focus on reforesting sites that have been harvested for BCTS and helping those new forests thrive.

On average, each silviculture forester like Fielding oversees the planting of approximately two million trees every year. To choose which species to plant, they conduct research into seed varieties, examine climate modelling, explore tree breeding and study and manage for forest health, aiming to maintain as much natural vegetation as possible. Gone are the days of reforesting with monocultures; foresters have learned over the years that single-species forests are not as resilient as those with varied trees types and ages. The more the merrier—their goal is to plant as many species as a site is likely to support.

After planting, professional foresters carefully monitor reforested areas, surveying them regularly to track growth progress and resilience to threats. They gather data and information to continuously improve their work and make good choices for BC’s forests.

“We aim for forests that support wildlife, riparian function, Indigenous cultural values and forest structure. Any day I get out in the field, I learn something,” Fielding adds.

BC has more certified forest land to care for than any other jurisdiction in the world, with the exception of Canada as a whole. The work of our provincial foresters is vital to maintaining this natural resource, especially given recent wildfires, droughts and heatwaves.

“We need forests that, 80 years from now, are going to be as resilient as possible to weather events and climate change,” Fielding says. “It’s very rewarding for me to see a healthy, forested site with trees that I played a role in planting years ago. It gives me a lot of confidence that the forest is going to be healthy and mature and will be available to support BC in the future. It makes me proud.”

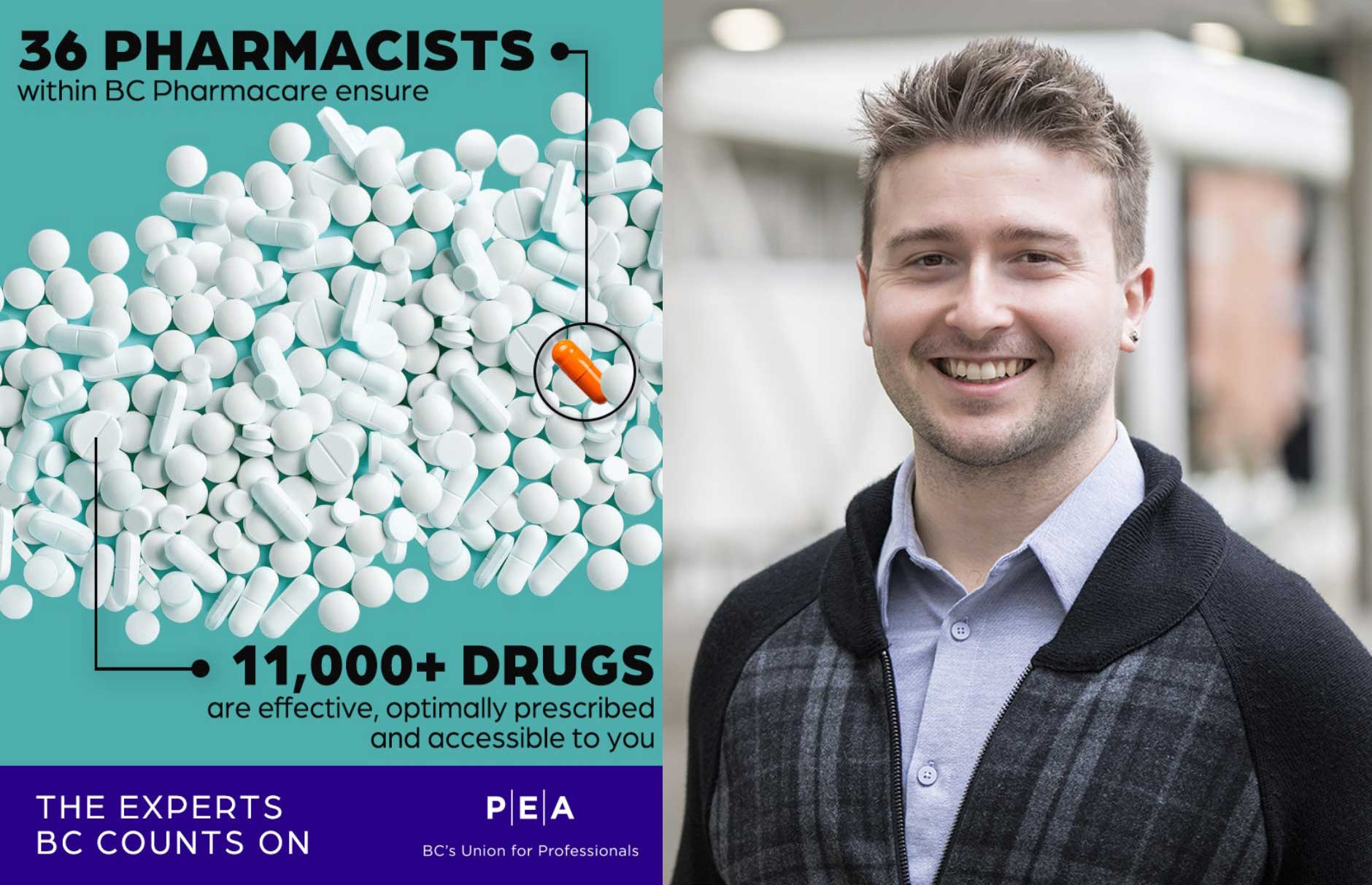

Pharmacists

Ministry of Health pharmacists make complex decisions about medications for the good of the province and its residents.

More than 11,000 medications and products were dispensed in British Columbia in 2023 to improve the health of patients. That’s a lot of medications for health care providers to stay on top of—to understand how to prescribe each of them, under what conditions they are most likely to work, and what the expected outcomes are.

Pharmacists are the medication experts of our healthcare system, providing trusted guidance on prescribing. Patients are most familiar with community pharmacists, who serve the public directly at drugstores and pharmacies where they are accessible and maintain relationships with the public.

But, working behind the scenes in the Ministry of Health are over 36 Public Service pharmacists , all members of the PEA’s Government License Professionals chapter.

These Public Service pharmacists are specialists in a range of pharmaceutical sciences, and their work supports their frontline counterparts. In addition to dispensing, they support the availability, funding, coverage and effective use of drugs in the province. For example, some oversee the list (called a formulary) of medications that are available through PharmaCare, BC’s publicly funded program that helps residents pay for many prescription drugs, dispensing fees and some medical devices and supplies. They ensure the medications are effective, prescribed optimally and available in BC, and they participate in the drug review process for new medications.

Other groups of ministry pharmacists help mitigate province-wide drug shortages; review data and ensure medications are used correctly to provide optimal results for patients; and dispense specialty medications to certain government programs, select patient populations, and health authorities. Furthermore, some Public Service pharmacists help people access the drugs they need through both PharmaCare and the Special Authority, the division that grants patients full or partial coverage of a drug or medical device that otherwise may not be covered by PharmaCare.

The work of this team is vital to ensure British Columbians have access to safe treatment options for their conditions. Their work aligns with the mission to be responsible to the residents of BC as a whole and to contribute to responsible and appropriate use of public funds.

Victoria-based Boris Trinajstic, one of the province’s 10 Special Authority pharmacists, explains a key difference between a pharmacist in a community drugstore or hospital and a pharmacist working for the BC Public Service:

“When you’re working in a pharmacy, whether a hospital or community setting, you’re heavily focused on individual patient care,” he begins.

“Working for the Ministry of Health, Special Authority pharmacists must also use a sizeable view; decisions around coverage get made on a case-by-case basis, but also have implications on the entire population level. We’re responsible to the residents of BC, and we have to be mindful of everyone. We need to consider precedent and responsible use of public funds when we make decisions around coverage.”

Special Authority pharmacists work collaboratively and consult with physicians and other medical experts in the field through Drug Benefit Adjudication Advisory Committees (DBAAC). The work of these committees often concerns high-cost medications, addressing case-by-case scenarios in which an individual is seeking access to medication not typically covered by the province. The committee recommends to the Special Authority pharmacist whether the medication should be covered by taking into consideration an array of available information, including clinical patient information, diagnostics and therapeutic expertise.

They also contribute to the drug listing process, working with their counterparts on the Formulary Management team to assist with the addition of new medications being considered for the provincial formulary.

Trinajstic is a third-generation pharmacist but the first to work in the Public Service. He graduated in 2020 from the University of British Columbia with a doctor of pharmacy, and, after working as both a community and hospital pharmacist, he opted to work for the Public Service in 2023, drawn to the broader allure of helping all British Columbians.

Keeping the big picture in mind during decision making is key to the role of the Special Authority pharmacist, Trinajstic says, but it needs to be balanced against the needs of individual patients.

“At the end of the day, we serve all BC residents,” Trinajstic says. “Our day-to-day work often involves the critical thinking, evaluation of information, and collaborative professionalism. Whether we are reviewing a case in our DBAAC committees, assisting with a new medication being listed or adjudicating day-to-day Special Authority requests, we want to make sure any precedent-setting decisions are going to have the best impact on individual patient care, but also the wider system, in an evidence-based manner. For instance, if providing access to a certain medication can result in lower healthcare costs and expenditure down the road, we will always take that into consideration when we look at case-by-case scenarios.”

“But at the same time,” he adds, “we have to be mindful of the broader scale and ensure that we are doing our part to contribute to responsible use of public funds. Our goal is to provide the best outcomes we can for not only our healthcare system or individual patients, but also for British Columbians as a whole.”

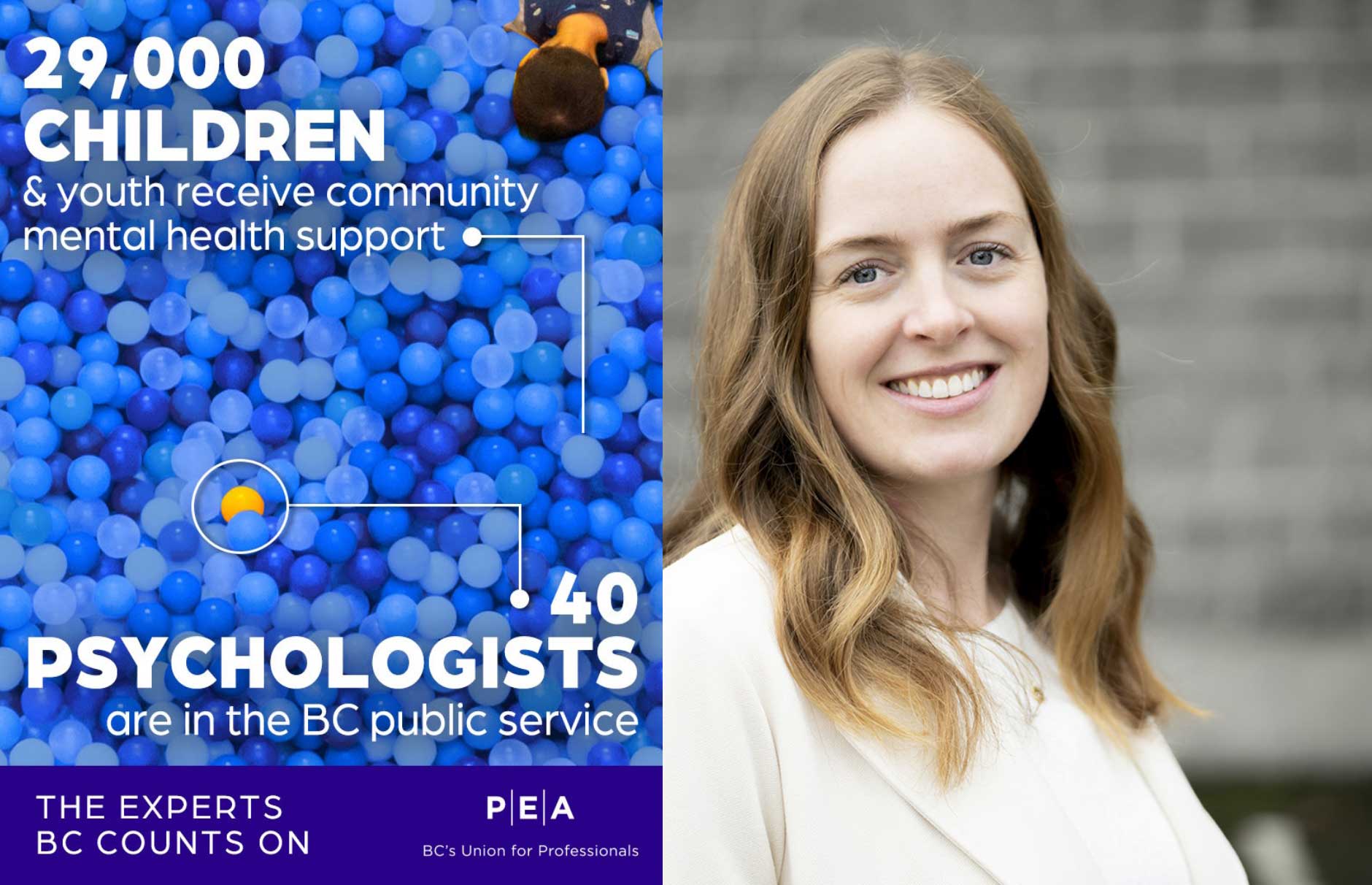

Psychologists: Supporting children for a stronger BC

Public access to free licensed psychologists provides early intervention for children and youth with mental health concerns.

When a child is facing a mental health issue, their whole community is affected. Parents and caregivers may be left feeling helpless, unable to alleviate their child’s pain. Teachers do what they can to encourage attendance and participation in school life, often to no avail. Siblings and classmates, too, feel the effects, as they struggle to build friendships and connect.

“Mental health doesn’t just impact the individual,” says Dr. Katherine Vink, a Victoria-based licensed psychologist with the Ministry of Children and Families (MCFD). “It is exceptionally heartbreaking to see a child struggling. The earlier we can intervene, the better the outcomes are for children. We can help set them up with skills and strategies to cope with challenging experiences and changes in their life.”

In British Columbia, there are approximately 40 public psychologists at MCFD who support children and youth with moderate to severe mental health issues. As PEA members and part of the Government Licensed Professionals chapter, these psychologists are highly trained, coming with at least 10 years of postsecondary education and 1,600 hours of clinical residency. Many of them operate out of child and youth mental health centres located throughout the province.

By the time a family arrives for intake, they have often tried everything to help their child, Vink explains. “You’re seeing people at their most vulnerable. It takes so much courage to ask for help.”

Families can refer themselves to child and youth mental health teams in MCFD; there is no intermediary or doctor’s referral needed. In the intake process, the child or youth will be assigned a psychologist, social worker or other clinician, depending on their need.

Often, licensed psychologists like Vink treat children with severe anxiety or depression and suicidal youth, many who have experienced significant trauma. Psychologists will conduct comprehensive psychological assessments to diagnose the child or youth and develop treatment plans that include evidence-based psychological interventions. Care is usually delivered in a mix of one-on-one sessions and in family and group therapy.

When treating a child and their family, compassion, respect and sensitivity are necessary, says Vink. Licensed psychologists practice in a trauma-informed way and adapt best practices for each patient’s situation, including their family, cultural or community contexts. Relationship building with the whole family is part of the approach and is essential to treatment.

“The psychologist helps the child’s inner circle understand what is happening and develop methods of management and coping,” Vink adds.

Without the service of licensed psychologists through MCFD, the health care system would be overburdened more than it already is. In BC, 70% of primary care visits are reported to be related to mental health issues.

Seeing a psychologist privately is cost-prohibitive for most families.

“The recommended rate in BC [for a private psychologist] is around $235.00 an hour,” Vink explains. “Being able to provide a publicly funded service [through MCFD] reduces barriers and allows people to access support.”

Communities across Canada are reporting a mental health crisis with rising numbers of children and youth facing complex issues. In BC in 2023/2024, MCFD reported serving more than 23,000 children and youth for mental health concerns.

For Vink, early intervention is key.

“If children can access timely and effective mental health treatment, the better off things are going to be for them in 10, 20, 30 years,” she says. “Psychologists have the skills and expertise to use therapeutic approaches and strategies that evidence tells us works for children and youth.”

Another aspect of the licensed psychologist role involves training future child and youth psychologists. MCFD developed a residency program that is nationally accredited.

“We’re supporting the future of the province when we invest in training psychologists,” Vink adds, noting MCFD has experienced difficulty recruiting and retaining licensed psychologists due to the significant pay discrepancy between public- and private-sector work.

Vink went through the MCFD training program in 2017/2018, while she was a doctoral student in clinical child psychology at the University of Alberta. After working at a hospital in Ontario for three years, she decided to return to Victoria and pursue her career with MCFD.

“I feel so privileged that children, youth and families put trust in me,” she says. “Children and youth are the future. We need to take care of one another in this society.”

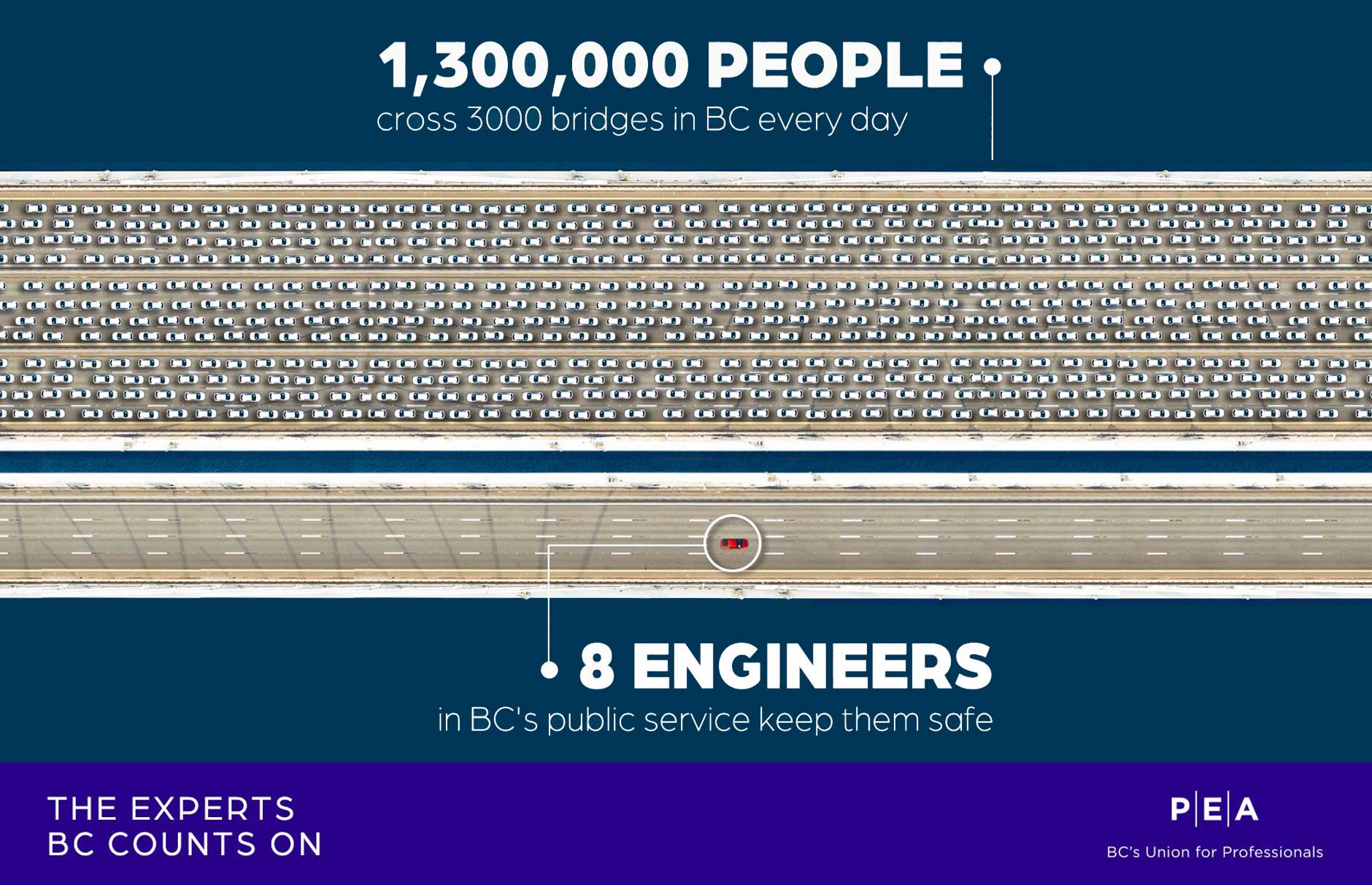

Engineers

Keeping BC’s roads, bridges and dams safe.

In 2002, the PEA joined three BC government engineers and the Minister of Public Safety at Bottletop Bridge, a critical piece of the Coquihalla highway between Hope and Merritt.

These engineers were an important part of the rapid emergency response during the flooding and landslides that severely damaged communities and roads throughout BC in 2021, impacting infrastructure that we all rely on.

During that time, they were on the scene assessing damage to the highway and then working long days on the structural and hydrotechnical engineering for new bridges that would allow the Coquihalla to reopen.

Without them, the province couldn’t have rebuilt the Coquihalla so quickly.

Engineers in the public service face significant recruitment and retention challenges, and these professionals are often overworked and underpaid. With climate change causing more frequent and severe weather events, it’s imperative that the BC government invest in its engineers and other public service professionals to ensure a safer, more resilient future.